A DELIGHTFUL FESTIVAL OF YOUNG PIANISTS IN OCTOBER

Yekwon Sunwoo, George Li and Zhang Zuo, piano: An October Pianofest, Chan Centre and Vancouver Playhouse, October 1st, 15th and 22nd, 2017.

The Vancouver Recital Society has always found stunning young pianists to display for us over the years, but this three-concert ‘pianofest’ stands right at the top of their endeavours. It featured Yekwon Sunwoo, Gold Medalist in the 15th Van Cliburn Piano Competition, George Li, Silver Medalist in the 2015 Tchaikovsky Competition, and Zhang Zuo, a former BBC New Generation artist and the winner of the China International and Gina Bachauer Competitions. There was plenty of variety in each recital, but the highlights were probably the more heavy-hitting pieces of Liszt and Rachmaninoff, full of power and engagement.

I unfortunately was only able to see the Zuo and Li concerts, but I have gleaned from many that Yekwon Sunwoo exhibited technical assurance in spades and a sterling sense of musical architecture, especially in his Rachmaninoff Sonata No. 2. George Li was a returnee: he first appeared here when he was 16 years old, and even then he displayed enviable keyboard control. I still fondly recall him sitting on the edge of the stage during the post-concert Q&A, attempting to answer discerning questions from the audience, his legs dangling back and forth hoping that someone would let him out to play very soon.

Well, Li is a full-fledged virtuoso now at age 22, capable of remarkable tonal sophistication and heaven-storming bravura. He gave a pretty gripping performance of the Rachmaninoff Corelli Variations, exhibiting sterling tonal control and finding cohesiveness in a piece that does not easily play itself. For all his precision and command, Li might be slightly too emphatic at times, but this was of little consequence for his stunning Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody No.2 at the close of the concert, which stormed from the gate with almost super-human address and dazzle, leaving everyone gasping for breath at the end. The weight and solidity which Li can draw from the piano is remarkable. His most beautiful playing was in the Liszt Consolation No. 3, where he showed a lovely identification with the composer’s soft lyricism.

The identification with Haydn and Chopin in the first half of the concert was not as complete. The Haydn Sonata in B minor was presented with obvious thought but Li’s phrasing and dynamics did not seem very natural. Some of his phrasing struck me as short-breathed, and the finale’s driving insistence seemed to only tangentially find the composer’s special type of wit. The Chopin Sonata No. 2 had some explosive rushes of adrenalin too, but the pianist seemed to respond more naturally to the brightly-lit moments than the work’s deep lyrical musing: the famous ‘Funeral March’ came off rather too studied and ponderous.

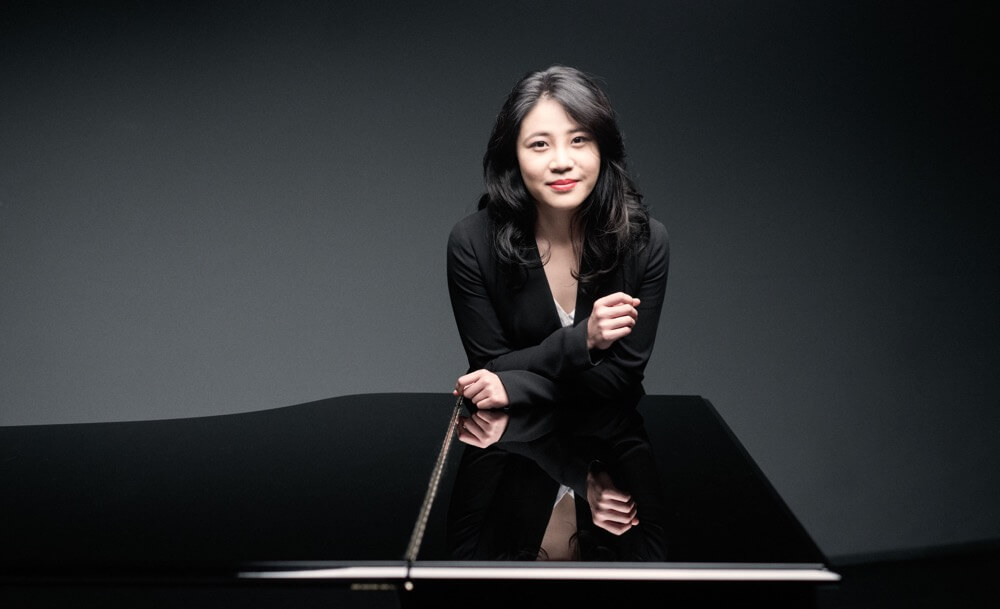

If George Li can dazzle and overwhelm with his technical prowess, while sometimes remaining exteriorized emotionally, Zhang Zuo (called ‘Zee Zee’) is almost the opposite. Her technique is less assured but her feelings are so transparent. There were many moments of communicative playing in each of her performances, even if a sort of bulkiness in execution set in at points. The best performance in terms of communicating musical line and emotional transparency was probably the closing Liszt Rhapsodie Espagnole: some unsophisticated pedaling aside, it had real engagement and found moments of special joy. This was wonderfully revealing of a young artist, bursting in insight, showing us her unique struggle to put her ideas together. In Liszt’s Vallée d'Obermann too, one could only be impressed by the extremes of volcanic weight and lovely soft playing that came forth.

In many respects, I thought Zee Zee communicated more insights than Li on the earlier works. Her Beethoven 32 Variations in C minor may have been big-boned and overly-passionate at times, but the pianist’s tonal variety and sense of line and contrast were always fully involving. Schubert’s C minor Sonata, D 958 is not for the meek, but her efforts were certainly a step in the right direction, with the proviso that this was still clearly a work in progress and there were technical imperfections. The opening Allegro may have had a certain jauntiness and reluctance to push forward lyrical ardour but I felt a fine human spirit in the playing. A good portion of the Adagio was impressive in its patience and inward feeling, while the Menuetto had an intelligent sense of structure and contrast. There was some feeling of jumpiness in the finale, and not all the wit was absorbed, but sometimes the pianist put her finger on a type of complexity in the musical argument that I had not previously thought of.

This was a most enjoyable little festival of ‘next generation’ talent – and certainly should be undertaken again. One clear observation from the two concerts I saw is that these young pianists all relish opening out the sound of the piano in the more heavy-hitting virtuoso pieces, while they often seem less absorbed and facile in the earlier classical/romantic repertoire. Perhaps that simply reflects the artists chosen here, or perhaps it reflects something deeper from a social perspective: that the perceived payoff to specializing in virtuoso pieces is higher than that of mastering, say, Mozart. I recall discussing something like this when I interviewed Paul Lewis a few years ago. He made a revealing point: the earlier, less ostentatious compositions put a glaring spotlight on what you, the pianist, are really made of. You can wear many different types of ‘clothes’ when playing the large stuff, but you are absolutely naked when playing Mozart. An insight that many a young pianist might absorb!

© Geoffrey Newman 2017