MONICA HUGGETT AND THE PACIFIC BAROQUE BRING JOSEPH BOLOGNE DE SAINT-GEORGES TO LIFE

Monica Huggett, Chloe Myers and Linda Melsted, violins, Pacific Baroque Orchestra/ Alexander Weimann, Music ofJoseph Bologne de Saint-Georges, Leclair, Mozart and Haydn, Playhouse, February 4, 2017.

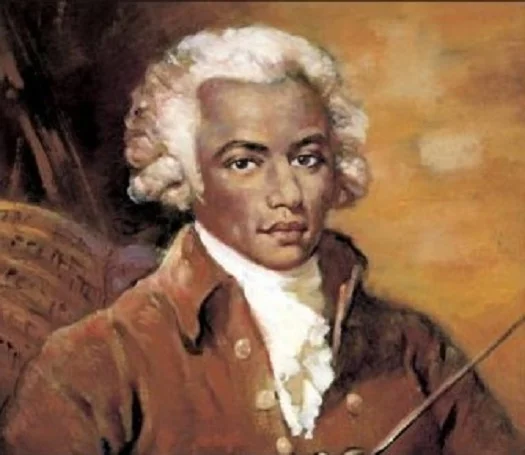

Over the past two decades, there has been a strong awakening of interest in the compositions of Joseph Bologne de Saint-Georges. The interest is perhaps more than just musical: there is a certain intrigue about a composer who was born in Guadeloupe in 1745, the offspring of a French plantation owner and a slave mother, and who gained the informal title of ‘Le Mozart Noir’. There can really be few comparisons in classical times, and not only because of Bologne’s African heritage: he was also a magnificent violinist and, yes, a master swordsman, sometimes deemed the greatest in Europe. After studies with the venerable Leclair, and mastering the violin with the same facility as the sword, he achieved a strong presence in Paris from the 1770s onward as a soloist, composer, and director of orchestras. He even commissioned Haydn’s ‘Paris Symphonies’. While Bologne had a fascination with the sinfonia concertante and the violin concerto (of which he wrote 21), it is arguably his later operas that stand as his greatest achievement. This concert offered a fetching slice of this unique period, with two violin works by the composer, a violin concerto by Leclair, one of the commissioned Haydn symphonies, and a Mozart’s own Symphony No. 5 of 1765.

One would presume that Mozart’s early compositions must have had some influence on the elder Bologne, but Mozart’s ‘Paris’ style is distinct, and it is well worth considering the possibility that the influence went the other way too. In fact, Bologne’s interest in writing sinfonia concertante predates Mozart’s famous K. 364 of 1779 by several years. On the surface, Bologne’s expositions can delight with their graceful and carefree amiability. Though some of his thematic efforts are not the equal of Mozart’s, what is interesting is how he sometimes follows his own passions: a sense of the operatic seems to imbue his tuttis, and his retreat to quieter moments can reveal flights of fancy. Constructional idiosyncrasies appear with a certain regularity, some of these illuminating, others less so.

Chloe Myers and Linda Melsted took on the composer’s two-movement Double Violin Concerto from Op. 13 to begin and it was quite apparent how much the rapport and phrasing of the two soloists shared the style of Mozart’s K.364. The start of the work was unusual since one violinist was given the stage for a long time before the second entered. While an air of pleasantness informed the proceedings, the composer’s modulations to the minor keys were noteworthy, taking the music into more enigmatic terrain. The closing movement also had a particularly good-natured feel, and surprised delightfully with its little cadential pauses. Other parts of the construction might have been a little ‘rough’, and the reliance on ostinato figures in building tuttis a little predictable, but the melodic inspiration was seldom in doubt. I found both soloists very sensitive to the individuality in this writing.

Monica Huggett took over the reins in the first of the earlier Violin Concertos, Op. 5, giving her well-known panoply of period violin techniques, ranging from double stopping to audacious slides, and much more that would have delighted a Parisian audience of the time. This was a more tight-knit, virtuoso work in general, less adventurous in melodic line and sometimes tending to the overly-rhetorical. Interestingly, the orchestra managed to build to climaxes of exceptional volume in the opening Allegro, reminding me even of Beethoven. The best movement was probably the Rondeau finale, having a charm, lyrical shape and ingenuity that was distinctive. Two works are hardly enough to fully introduce this composer to the audience but they certainly made a convincing case for exploring him further.

Possibly the gem of the night turned out to be Huggett’s rendering of the first of the Violin Concertos, Op. 10 by Bologne’s teacher, Jean-Marie Leclair. The violinist achieved lovely poise and élan in the solo part, and secured sparkling orchestral cooperation. The work has its virtuosic moments, yet a cunning compositional balance too, and it was the sheer flow and shape of this reading that made it come off so well. I also enjoyed hearing Mozart’s Symphony No. 5, which was delivered with a nice tight-knit energy and integration. Haydn’s famous ‘La Reine’ Symphony (1785) is likely one of the biggest works that Pacific Baroque has ever tried: extra winds and horns had to be brought in for the occasion. Fine buoyancy was achieved in the opening movement, particularly emphasizing the reference to the composer’s earlier ‘Farewell’ Symphony, but a hint of caution set in fairly quickly. The Romance was over-conscientious and lacked natural flow while the finale stressed precision over lightness and wit. This was enjoyable enough but, with all the adaptations needed to facilitate the added players and the like, I think it stubbornly remained a work in progress for the group.

Early Music Vancouver deserves great praise for presenting a programme that really illumined the cross-fertilization of musical impulses in a period that is not always explored. If discovering Joseph Bologne turned out to be inspiring, then one can only imagine other contemporaries that might be waiting to be unearthed as well.

© Geoffrey Newman 2017