THE BEAUTIFULLY-TONED BENNEWITZ QUARTET CARRY ON A CZECH TRADITION

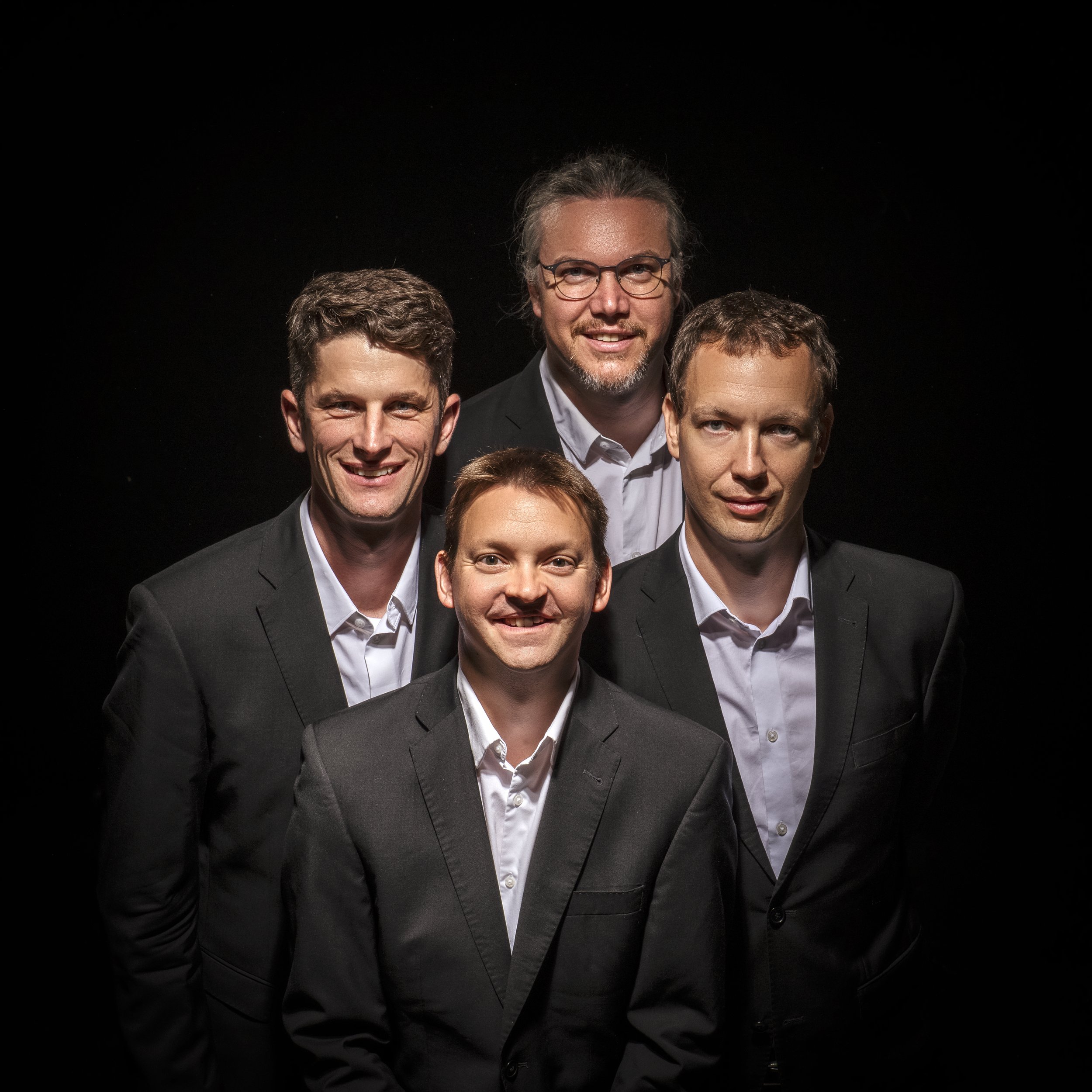

Bennewitz Quartet (Jakub Fišer and Štěpán Ježek, violins, Jiří Pinkas, viola, Štěpán Doležal, cello): Works by Janáček, Schumann, and Dvořák, Playhouse, October 13, 2019.

Vancouver’s Friends of Chamber Music has long sponsored the finest Czech string quartets: the legendary Smetana and Talich Quartets appeared in earlier days, and the venerable Pražák Quartet has now visited for three decades. Of the younger ensembles, the celebrated Pavel Haas Quartet makes its fourth visit later this season while the young Zemlinsky Quartet appeared with the Pražák last year. Which leaves the Bennewitz Quartet, who made their debut on this occasion. This ensemble was formed in 1998 and, initially, won two important string quartet competitions: the Osaka in 2005 and Prémio Paolo Borciani in 2008.

The Bennewitz Quartet exhibits all the trademark rhythmic address and strong accents of Czech string playing, but distinguishes itself as considerably warmer and more fulsome than many of its predecessors. Overall, the ensemble produces a most beautiful sound: each instrumentalist has their own distinct timbre and forms part of a strong corporate blend. Another defining characteristic is the ensemble’s natural sense of rhythmic flow; its patience in articulation possibly takes one back to the Stamitz Quartet. Janáček’s String Quartet No. 2 received the most striking reading here, wedding luxuriant textures with a strong expressive flow to produce something quite different than the more astringent treatments one often hears. Schumann’s Quartet No. 2 had fine motion and architecture, while the ever-popular Dvořák ‘American’ Quartet completed the programme with Czech writing at its most characteristic.

Both of Leoš Janáček’s string quartets were written in 1923, and masterfully explore the conjunction of deep melancholy with more demonstrative expressions of inner turmoil. One notable technical characteristic is the extensive use of ponticelli (bowing across the bridge) to convey either a mysterious foreboding or a more visceral physical threat. Each quartet responds to a profound sense of loss. The second, ‘Intimate Letters’, is the composer’s last work, an autobiographical disquisition on a consuming past love, and impresses with how forward looking its construction is. In the hands of the original Janáček Quartet and, later, the Talich Quartet, the composition has both a striking sharpness of utterance and a special intimacy, where all the ponticelli interjections almost seem to summon voices from another world. The Bennewitz performance, however, was different: following the work’s narrative closely, the group employed unusually rich, flowing textures to suspend the listener almost cinematically in the varied contours of the composer’s emotional journey. The burnished weight of this performance recalled the post-romantic luxuriance and sensuality of Schoenberg and Zemlinsky around the turn of the century. The dialogue between the voices was generally subtle and rounded, rather than cuttingly etched, and the stabbing ponticelli stood out less.

Photo Credits: Petra Hajska, Milan Mosna

The first two movements were taken at a deliberate pace, rich in colour but always inward looking. The early solo viola, beautifully presented by Jiří Pinkas, was more musing, as if in a deep reverie, while sharper dramatic contrasts were subsumed into to an undulating melancholic flow. The gentle, inexorable tread was strong in character and very successfully held together. The apex was the Moderato, where all the feelings of (past) love just poured out uncontrollably. Led by the strength of Jakub Fišer’s violin, this was almost overwhelming both in its heartfelt beauty and feeling and in the sheer weight and amplitude of the group’s sound. It was the defining moment of the work. The closing Allegro largely maintained this concentration, finding a sense of regret no matter how demonstrative the assertion, being only slightly less at home in the quiet, pizzicato passages at the end. An unconventional slant on this work, but one which had consistency and integration, was fully gripping in its emotional reach and honesty, and featured playing of the greatest beauty.

After hearing the first of Schumann’s three Op. 41 quartets so frequently, it was rewarding to start the concert with a performance of No. 2. (He wrote all three quartets of Op. 41 in a span of three weeks in June 1842.) This is a more tightly structured composition than No.1, and the Bennewitz Quartet endowed the opening Allegro with a finely-balanced architecture, a coaxing underlying lyrical flow and an estimable tonal blend. There was an appealing mix of sforzandi emphasis and gentle frolic, and the pianissimo passage just before the end was negotiated tellingly. The subsequent movements had well-chosen tempi and admirable appointment, but it sometimes seemed that the style was a little heavy for Schumann. Thus, the Scherzo had had an earthy, bucolic weight slightly outsize for the composer, while the rhythmic drive and colour in the finale perhaps reminded me more of Dvořák than the finer-drawn lines of the work’s dedicatee, Mendelssohn. Still, a most enjoyable effort, with considerable joy and freedom in the playing, just short of being fully idiomatic.

Dvořák’s ‘American’ Quartet has naturally been the ‘go to’ closing work for Czech ensembles, full of beguiling rustic energy and feeling. Performances are thick on the ground, ranging from the classic Janáček Quartet reading a half-century ago to the prize-winning modern account from the Pavel Haas Quartet. The Bennewitz’s performance featured fine energy and distinguished playing but, in the final analysis, did not yet capture the work’s full character and charm. I found it a very earnest, but slightly grounded, reading.

One thing evident from the earlier Janáček performance is that the ensemble loves full-out romantic expression – but perhaps it was too much of a good thing in Dvořák. The ensemble pushed into the famous Lento with the most passionate expression possible but did not really make room to register the contemplative stillness of a dumka. The playing was indeed commanding but the tempo was just fractionally too fast to ‘seat’ the movement and generate repose: it seemed to get even faster in the more urgent moments. Something of the same tendency was present in the opening Allegro, where the second subject was given full romantic treatment, but what preceded and followed it was rhythmically rather straitlaced. Surely there is more delight, charm and frothiness in these sections too – but the first violin’s inflections did not capture all the romantic caprice. The same for the beginning of the Finale, where the leader did not find all the dancing joy and flexibility of line implied. The close of the work had great energy but I would hesitate to call it uncontrolled elation. These are small critical points but, overall, the group seemed to focus on the more obvious dimensions of romantic feeling and rhythmic energy without finding the all the imaginative depth in the work’s expression. Perhaps that’s what being a ‘young’ quartet means.

Following on the Pavel Haas Quartet’s lead in performing the neglected works of Czech Holocaust composers, it was most worthwhile to hear the enigmatic ‘Tango’ from Erwin Schulhoff’s Five Pieces for String Quartet as an encore. The Bennewitz Quartet has shown the greatest commitment to these often-forgotten composers and this piece was an extract from their just-released Supraphon recording of the string quartets of Ullmann, Krása, Schulhoff and Haas.

© Geoffrey Newman 2019